Most people believe museums are neutral containers of truth, but this is a fundamental misunderstanding. Every exhibit is a carefully constructed argument. This guide reveals the curatorial secrets to deconstruct that argument, helping you see the hidden narrative shaped by what is shown, how it’s shown, and most importantly, what is left out entirely. You’ll learn to analyze an exhibit not as a collection of objects, but as a deliberate story with its own biases and intentions.

There’s a familiar feeling that settles in after an hour in a great museum: a sense of being both inspired and overwhelmed. You’ve dutifully read the wall texts, admired the masterpieces, and yet, a nagging feeling remains. Are you missing something? The common advice is to “ask questions” or “look closer,” but these suggestions are vague. They don’t equip you to penetrate the surface of an exhibit. As a curator, I can tell you that an exhibit is more than a collection of artifacts; it is a piece of theatre, a work of non-fiction, and an argument, all at once. The objects are the words, but the layout, lighting, and omissions form the grammar and syntax.

But what if the key to a truly profound museum visit wasn’t just about appreciating the objects, but about deconstructing the very “Narrative Architecture” that presents them? The real story isn’t just in the artifacts themselves, but in the web of decisions that brought them before your eyes. It’s about understanding the curatorial gaze, the institutional voice, and the economic and political forces that shape what histories are told and which remain in storage. This is the art of reading between the lines.

This guide will move you from a passive observer to an active reader of museum spaces. We’ll explore how to identify the subtle misinformation of omission, decode the meaning of empty space, and understand the ethical dramas playing out behind the scenes through repatriation. By learning to see the exhibit as a constructed text, you transform a simple visit into a deep, critical, and unforgettable experience.

To navigate this journey, this article breaks down the essential skills and contexts needed to decode a museum’s hidden language. The following sections will guide you through the layers of meaning, from the power of narrative to the practicalities of planning your critical exploration.

Summary: Decoding the Unseen Layers of a Museum

- Why Misinformation Spreads 6 Times Faster Than Truth?

- How to Make History Fun for Kids Without Boring Them?

- Minimalist Sets: How to Read Meaning in Empty Spaces?

- Why Museums Are Returning Artifacts to Countries of Origin?

- Why You Cannot Take Flash Photos of Ancient Textiles?

- The ‘Museum Fatigue’ Cure: Planning Your 2-Hour Route

- Annual Pass vs Day Ticket: When Does It Pay Off?

- How to Buy Your First Original Artwork Without Getting Ripped Off?

Why Misinformation Spreads 6 Times Faster Than Truth?

In an age of rampant digital falsehoods, museums are often seen as bastions of truth and authenticity. They present physical evidence of history, seemingly immutable and real. However, this perception overlooks a more subtle form of misinformation: the sin of omission. An exhibit, by its very nature, is a selection. For every object on display, hundreds or even thousands lie in storage. The narrative you see is not the whole story; it is one story, curated and framed with a specific intention. Understanding this is the first step in critical museum literacy.

This curatorial selection process, while necessary, can inadvertently perpetuate a skewed version of history. When an exhibit on industrial innovation only shows the triumphs of inventors without acknowledging the exploited labor that made it possible, it isn’t lying, but it isn’t telling the whole truth either. The post-pandemic recovery, which has seen museums experiencing an average of 71% of their previous attendance, highlights their continued importance. Visitors are returning, hungry for authentic connection and knowledge. This presents a crucial opportunity to foster a more discerning audience.

The antidote to this passive misinformation is not to distrust museums, but to engage them critically. It involves actively questioning the “curatorial gaze.” Why were these specific objects chosen? Whose story do they tell? And, most critically, whose story is missing? As one study on visitor engagement notes, museums are increasingly committed to supporting the needs and agency of their visitors. True agency begins when you recognize the exhibit not as a static collection of facts, but as a dynamic argument you are invited to question, analyze, and complete with your own knowledge.

How to Make History Fun for Kids Without Boring Them?

Teaching children to “read between the lines” of a museum is one of the most powerful ways to cultivate lifelong critical thinking. The key is to transform the visit from a passive lesson into an active investigation. “Fun” in this context isn’t about trivial games; it’s about empowerment. When a child feels like a detective uncovering secrets, they are no longer being lectured to—they are constructing knowledge themselves.

The goal is to give them tools to deconstruct the exhibit. Instead of saying, “Look at this old pot,” ask, “If this pot could talk, what story would it tell? Who do you think was left out of its story on the label?” This shifts their focus from passive reception to active interpretation. A successful case study comes from the Boston Children’s Museum, which created meaningful climate change programming by using hands-on activities and brainstorming sessions. This model proves that engaging with complex topics is possible when children are given agency and a solution-based framework.

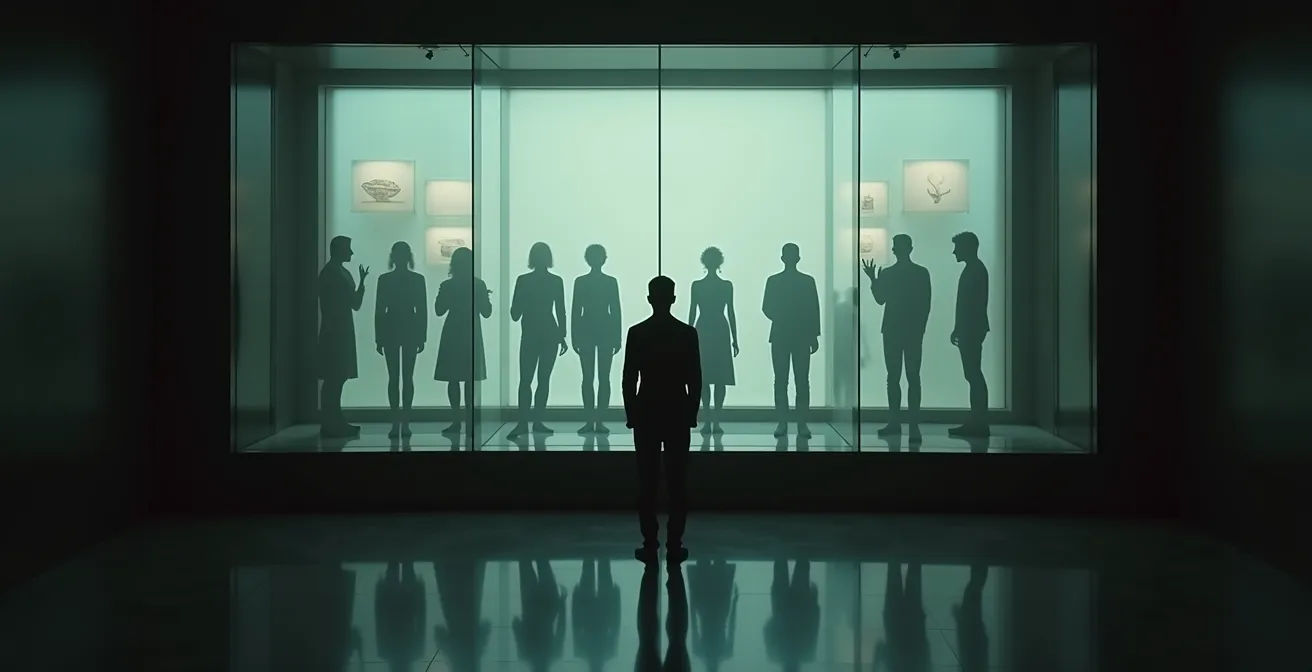

As the image above suggests, the right tools—whether a magnifying glass or a set of clever questions—can unlock a world of wonder. The goal is to make the child a co-curator of their own experience. This not only makes history more memorable but also instills a fundamental media literacy skill: understanding that every story has an author, and every author has a perspective.

Action Plan: Cultivating a Young Detective’s Eye

- Mystery Object Investigation: Find an object with a vague label. Have children use observation skills alone to invent its purpose, its user, and its story.

- “Yes, and…” Storytelling: Pick an artifact and start a story about its journey (“This sword was once owned by a pirate…”). Each person adds a sentence, building a collaborative, imaginary provenance.

- Museum Detective Badges: Create a scavenger hunt where kids find “contradictions” or missing perspectives, like finding a war exhibit with no mention of civilians, or a domestic scene showing only women.

- Timed Observation Challenges: In a busy gallery, give teams two minutes to find the most surprising or hidden detail in a large painting or diorama. This hones their visual scanning skills.

- Curator for a Day: Ask children what object they would add to an exhibit to tell a more complete story, or which object they would remove and why. This introduces the concept of curatorial choice.

Minimalist Sets: How to Read Meaning in Empty Spaces?

In a museum, what isn’t there is often as important as what is. Curators call this “the voice of absence,” and it is one of the most powerful, yet overlooked, aspects of exhibition design. A minimalist gallery with a single object in a large room or an empty display case is not a failure of curation; it’s a deliberate statement. The empty space acts as a frame, forcing your attention and inviting you to question the significance of both the object present and the objects absent.

This void can tell many stories. It might represent the fragility of an object, the irretrievable loss of history, or a political statement about a stolen artifact. The very existence of vast storage facilities, where countless “forgotten artifacts lay dormant,” confirms that every display is a choice to elevate one story over another. The empty space is a tribute to all the stories that could not be told within those four walls. It prompts the critical visitor to ask: What is this silence saying?

For example, an exhibit on a historical event that leaves a display case empty with a label reading “Artifacts from this village were destroyed” speaks volumes more about the totality of the loss than a case full of objects would. Reading meaning in these spaces requires a shift in perspective. You must stop looking for *things* and start looking for *relationships*—the relationship between the object and the space, the space and the light, and the entire room and the narrative of the exhibition. The space itself becomes an artifact, a testament to choices, losses, and priorities.

Why Museums Are Returning Artifacts to Countries of Origin?

The global movement for the repatriation of cultural property is perhaps the most dramatic and public example of “reading between the lines” of a museum’s collection. For centuries, the provenance—an object’s history of ownership—was a dry, academic detail. Today, it has become a central plot point in the story of major museums. The presence of objects like the Benin Bronzes or the Elgin Marbles in European museums is no longer seen as a simple fact of history, but as a contentious statement about power, colonialism, and ownership.

This debate forces us to deconstruct the very foundation of older collections. When you see an artifact from a distant land, the critical question is no longer just “What is this?” but “How did it get here?” Was it acquired through a legal purchase, a scientific excavation, a colonial seizure, or outright looting? The answer fundamentally changes the object’s meaning. The scale of this issue is staggering; an analysis reveals the total value of the illicit trade with existing records is around $2.5 billion, and this only scratches the surface. This isn’t just about art; it’s about reclaiming heritage.

This shift in consciousness is reshaping international law and museum ethics. As international law scholar Catharine Titi states, the landscape is changing profoundly:

Repatriation efforts are changing attitudes dramatically, with a new rule of international law emerging that requires the return of important cultural property to its country of origin if unlawfully or unethically removed.

– Catharine Titi, International Law Scholar

When a museum returns an artifact, it is actively rewriting its own narrative. It is an admission that the old “curatorial gaze” was flawed and that the stories of other cultures cannot be “owned.” For the visitor, understanding this context enriches the viewing of any non-local artifact, transforming it from a beautiful object into a complex symbol of global history.

Why You Cannot Take Flash Photos of Ancient Textiles?

The ubiquitous “no flash photography” sign in a museum gallery is more than just an annoying rule; it is a visible manifestation of a museum’s core, and often conflicting, mission. On one hand, a museum exists to provide public access to cultural heritage. On the other, its primary duty is the long-term preservation of that heritage. The prohibition of flash photography, especially around sensitive materials like ancient textiles, watercolors, and manuscripts, is where these two missions collide.

The reason for the rule is simple science. Light, particularly the intense, high-energy burst from a camera flash, is a form of radiation. Over time, cumulative exposure to light causes irreversible damage. Colors fade, and organic fibers in textiles and paper become brittle and disintegrate. A single flash may seem harmless, but the accumulated effect of thousands of flashes per day would rapidly destroy these fragile objects. As museum professionals know, the vast majority of collections are kept in dark, climate-controlled storage precisely to protect them from constant exposure to light and other environmental threats.

Understanding this rule is a lesson in reading a museum’s institutional priorities. It tells you that the long-term survival of the artifact is valued more highly than the visitor’s desire to create a perfect digital copy. It is a quiet assertion of the curator’s role as a steward. Instead of being frustrated by the limitation, a critical visitor can use it as a prompt. Why is *this* object under such strict protection while the bronze statue next to it is not? The answer reveals the object’s material vulnerability and, by extension, its preciousness. It encourages alternative, deeper forms of engagement, like sketching the object or writing detailed descriptive notes, forcing a slower, more deliberate act of looking.

The ‘Museum Fatigue’ Cure: Planning Your 2-Hour Route

“Museum fatigue” is a real phenomenon, but it’s not just about tired feet. It’s a cognitive-emotional exhaustion that stems from information overload and decision paralysis. Faced with thousands of objects, the brain shuts down. The cure, from a curatorial perspective, is not to see more, but to see more strategically. The ultimate act of “reading” a museum is to curate your own visit. By planning a route, you are imposing your own narrative onto the institution’s, transforming a passive experience into an active one.

Instead of wandering aimlessly, create a plan. This could be a “Thematic Sprint,” where you only visit objects related to a single theme (e.g., “power,” “motherhood,” “trade”) across different galleries. Or you could use the “Anchor Object Method,” choosing three to five key pieces in advance and dedicating your time to deep analysis of just those few. As a UK science museum study found, providing visitors opportunities to exercise agency and take control dramatically increases engagement and enjoyment. Planning your route is the ultimate exercise of that agency.

The architecture of the museum itself often guides you along a pre-determined path—a “narrative architecture.” By creating your own route, you break free from this intended flow and make new connections. The table below outlines a few strategies to take control of your visit.

| Strategy | Time Required | Engagement Level | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic Sprint | 90-120 minutes | High | First-time visitors seeking focus |

| Anchor Object Method | 60-90 minutes | Very High | Repeat visitors wanting depth |

| Architecture Reading | 45-60 minutes | Medium | Design enthusiasts |

Annual Pass vs Day Ticket: When Does It Pay Off?

The decision between buying a day ticket and investing in an annual pass may seem purely financial, but it has profound implications for how you learn to read a museum. A day ticket encourages the mindset of a tourist: a desire to “see everything” in one go, leading to the very museum fatigue we’ve discussed. It’s a transactional relationship. In contrast, an annual pass transforms your relationship with the institution. It is an investment in critical visual literacy.

With an annual pass, the pressure to conquer the entire museum vanishes. You can visit for just one hour to see a single gallery. You can return to a favorite painting multiple times across different seasons, seeing it in new light. You can attend special exhibits and lectures, gaining deeper insight into the curatorial process. This repetition and focused attention are essential for moving beyond the surface level. It allows you to notice subtle changes, understand the museum’s “voice,” and build a genuine, long-term intellectual relationship with the collection. The average US household spends a significant amount on entertainment, but the value of a museum pass transcends simple admission.

Essentially, the pass holder evolves from a consumer of culture into a student of it. They have the freedom to treat the museum like a library—a resource to be revisited, studied, and understood in depth over time. Considering that households with higher education levels spend significantly more on these experiences, it’s clear there’s a recognized link between sustained engagement and cultural spending. An annual pass is the most effective tool for facilitating that sustained, critical engagement.

Key Takeaways

- An exhibit is a constructed argument, not a neutral collection of facts; your role is to deconstruct it.

- What is absent (the “voice of absence”) is as meaningful as what is present; empty space tells a story.

- Understanding an object’s provenance (how it got there) and the ethics of repatriation is crucial to reading its full story.

How to Buy Your First Original Artwork Without Getting Ripped Off?

After learning to deconstruct museum exhibits, you’ve unknowingly acquired the foundational skills needed for a far more personal endeavor: collecting art. The critical lens you’ve developed for analyzing a curator’s choices is directly transferable to evaluating a piece of art for purchase. Moving from museum visitor to art buyer is the ultimate application of your new-found visual literacy. You are no longer just reading someone else’s narrative; you are starting to build your own.

The intimidating world of the art market becomes far more navigable when you apply the principles of museum analysis. The questions are the same, but the stakes are personal. Instead of questioning a museum label, you are scrutinizing a gallery’s claims. Is the story of this artwork credible? Who has owned it before? Is its physical condition sound? What makes it significant in the broader context of art history?

The skills you’ve honed are your best defense against getting ripped off. The process of “reading” a museum has trained you to look for the same things a savvy collector does. The following table makes this connection explicit, showing how your museum skills translate directly to smart art buying.

| Museum Skills | Application to Art Buying | Key Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Provenance Research | Verify ownership history | Who owned it? Where has it been? |

| Condition Assessment | Evaluate physical state | Any damage or restoration? |

| Cultural Context | Understand significance | Why does this matter? |

| Comparative Analysis | Assess fair pricing | How does it compare to similar works? |

Frequently Asked Questions on Museum Engagement

What are the typical cost ranges for annual museum passes?

Individual annual passes typically range from $220-$250, while family annual passes (2 adults, 4 children) cost approximately $320-$380.

What additional benefits come with annual memberships?

Annual members often receive discounts in gift shops and cafés, invites to members-only events, free or discounted parking, and reciprocal benefits at other museums through programs like NARM or ASTC.

How does education level affect museum spending?

College-educated households spend 5.2 times more on museum and entertainment fees ($1,645 on average) compared to households without a college graduate ($315 on average).

The next time you walk into a gallery, you won’t just be a visitor; you’ll be a reader. Begin deconstructing the narratives around you, questioning the empty spaces, and appreciating the complex journey of each object. This is how you discover the stories hidden in plain sight.